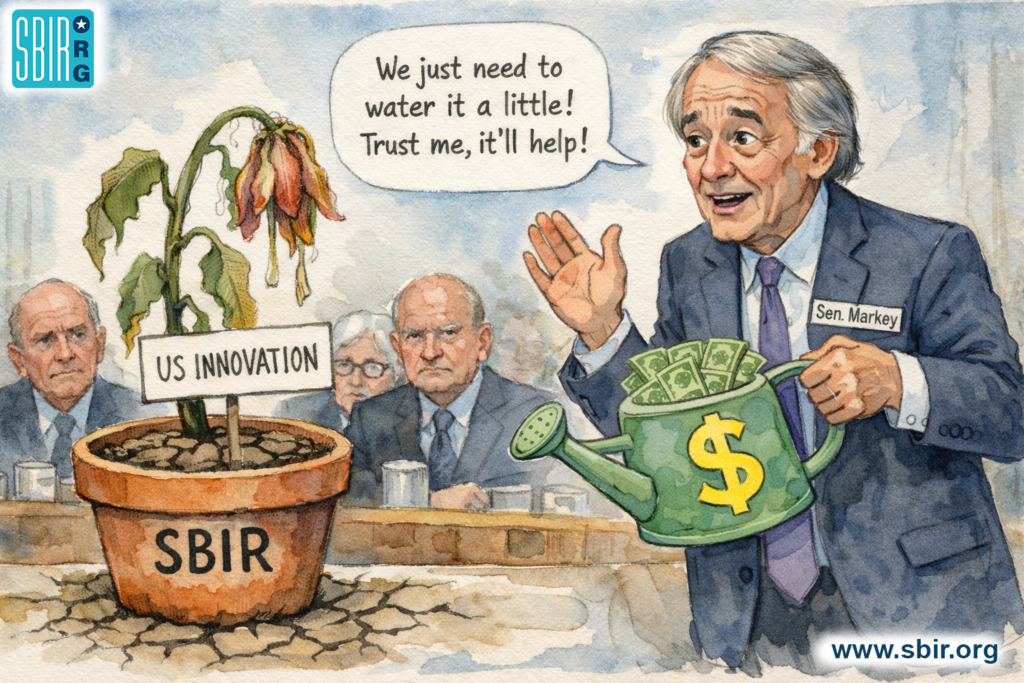

2026 Senate Bill Aims to Rescue SBIR Program

WASHINGTON — Jan. 7, 2026 — The nation’s premier small-business research grant programs remain in legislative limbo as lawmakers race to revive them before a fast-approaching funding deadline. The Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) and Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) programs – a 40-year-old “America’s seed fund” that has fueled cutting-edge R&D at startups – authority expired on September 30, 2025 after Congress failed to reauthorize them(**). Now, with a potential government shutdown looming on January 30, lawmakers are scrambling for a breakthrough. A last-ditch compromise bill released/circulated as a draft in December by Senator Edward J. Markey, Democrat of Massachusetts, seeks to end the impasse with reforms meant to address the national security and accountability concerns raised by Senator Joni Ernst, Republican of Iowa, whose objections have stalled the programs’ renewal(**).

A Compromise Bill Targets Security and “SBIR Mills”

Mr. Markey’s draft legislation – titled the “SBIR/STTR Reauthorization Act of 2025” (which you can read in its entirety at the bottom of this post) – pairs a multi-year extension of the programs with a suite of new provisions designed to answer Ms. Ernst’s criticisms. Notably, it would eliminate the programs’ sunset clause, effectively making SBIR and STTR permanent unless Congress acts to end them. The draft would raise the SBIR set-aside from 3.2% to 7% by FY2032 (and STTR from 0.45% to 1%), though the schedule in the draft excludes NSF and NIH. That increase is intended to expand opportunities for small firms – a priority long sought by program champions – even as the bill tightens oversight to ensure those dollars are well spent.

Several key reforms in Mr. Markey’s compromise directly respond to issues Ms. Ernst highlighted:

- Major anti-espionage safeguards: The bill extends to Sept. 30, 2045, a pilot “due diligence” program requiring agencies to screen SBIR applicants for national security risks. It directs agencies to apply uniform standards when vetting companies for ties to foreign adversaries. If a small business is deemed a security risk, agencies must notify the firm and allow it to mitigate concerns before denying an award. This provision aims to close what Ms. Ernst called dangerous “loopholes” that allowed China to exploit SBIR and “steal sensitive technology” developed with U.S. tax dollars(**).

- “Strategic breakthrough” awards for critical tech: To accelerate the transition of lab innovations to the field – especially for defense and health agencies – the bill creates a new class of Phase II “Strategic Breakthrough” grants. Large agencies with SBIR expenditures over $100M, like the Pentagon, NASA, Energy, NIH, and NSF, would be authorized to devote a small portion of their SBIR funds (up to 0.25% of their R&D budgets) to big-ticket awards as high as $30 million. These awards, which can run up to four years, must be matched dollar-for-dollar with non-SBIR funds (at least 20% of the match coming from government sources). Only firms that already proved their merit with a prior Phase II can apply, and they must demonstrate a clear path to deploy the technology – such as a military acquisition program or private commercialization plan. The idea, borrowed from Ms. Ernst’s proposal, is to “move our most promising technologies out of the lab and into production” for warfighters and other end-users(**). By requiring agency buy-in and matching investment, the awards seek to ensure “every dollar” advances real-world innovation, not just research papers. This authority would sunset on September 30, 2029.

- Crackdown on repeat grant “mills” without results: Perhaps the most significant reform is a new performance benchmark aimed at so-called “SBIR mills” – a small number of companies that gobble up federal grants but never fully commercialize their research. Under Mr. Markey’s bill, any company that won more than 50 Phase I awards in the past three years would have to show it’s delivering outcomes beyond just more government R&D. Specifically, such high-volume awardees must certify that at least 25% of their revenue comes from Phase III contracts or other non-SBIR sources (averaged over three years), or alternatively that 20% of their revenue since founding has come from non-SBIR/STTR work. Firms that fail to meet these commercialization benchmarks would face limits: in the next year, they could submit only about one-third of their usual number of Phase I proposals (their prior three-year application total divided by 3.5). This rule is essentially a pressure tactic to prevent abuse of the program as a “taxpayer-funded ATM” for perpetual researchers. It echoes Ms. Ernst’s complaints that some outfits have treated SBIR “like a private…grant-writing business” that churns out “nothing more than policy white papers” rather than usable technology(**). By tying continued participation to real-world revenue or Phase III follow-on work, the reform incentivizes serial SBIR recipients to actually bring products to market or partner with outside investors. (Agencies could waive the restriction for topics vital to national security, ensuring truly critical research isn’t arbitrarily shut out.)

- Expanded oversight and transparency: The compromise legislation layers in new oversight measures to track progress and prevent waste. It mandates improved data collection on commercialization outcomes and requires annual reports to Congress on key metrics. A comprehensive Government Accountability Office review of SBIR outreach efforts is also commissioned. Additionally, the bill raises the cap on agency administrative spending for the program – from 3% to 3.3% of SBIR funds – and extends this allowance for 20 years. That change gives agencies slightly more resources (funded out of SBIR itself) to police fraud, expedite awards, and assist small firms. There’s even a clause barring political appointees from meddling in award decisions, a “politicization prohibition” seemingly aimed at keeping merit review free of partisan influence. All told, these steps align with Ms. Ernst’s push to “ensure maximum impact of every dollar invested” in the program(**). By boosting oversight, Mr. Markey’s camp is addressing concerns that SBIR had too little accountability during its rapid growth.

- Opening doors for new and rural innovators: While security and efficiency are the headline issues, the bill also includes measures to broaden participation in SBIR/STTR – a traditional bipartisan goal. It would launch SBIR/STTR fellowship programs to cultivate young science talent and entrepreneurs at universities and labs. It also directs agencies to step up outreach in rural areas and underrepresented regions, coordinating with Small Business Administration partners to help rural firms compete for awards. Lawmakers from both parties have noted that SBIR awards tend to cluster in a few states and tech hubs; Ms. Ernst, who represents Iowa, welcomed language to “enhance…outreach to rural areas” so flyover-state startups aren’t left behind. Such provisions, while lower-profile, could help build broader support for the reauthorization by appealing to members far from the coastal R&D centers.

Taken together, Mr. Markey’s compromise bill represents a concerted effort to resolve the two issues Ms. Ernst cited for withholding her support: the threat of Chinese espionage siphoning off U.S. innovations, and the inefficiencies of a program she argues has been “gamed” by a handful of repeat contractors producing scant returns. “No more waste. No more giveaways to Beijing,” Ms. Ernst declared in a floor speech back in September, insisting on reforms before reauthorizing SBIR. Mr. Markey’s legislation pointedly addresses both refrains. It carries forward stringent foreign influence checks introduced in the last reauthorization and adds uniform standards to “ensure we…are not serving as a subsidy for Beijing,” as Ms. Ernst put it. And by establishing commercialization benchmarks and hefty “Phase II+” awards to push innovations out the door, the bill strives to refocus SBIR on tangible outcomes for defense and commerce – answering Ms. Ernst’s call to get beyond a “paper army” of reports and deliver “the technologies of tomorrow” to those who need them(**).

Whether these compromises go far enough to satisfy the Iowa Republican remains an open question. Notably, Mr. Markey’s draft omits some of the most aggressive curbs from Ms. Ernst’s original SBIR overhaul bill. For example, Ms. Ernst’s proposed lifetime cap of $75 million per company in SBIR Phase I/II funding – a hard ceiling to prevent any firm from endlessly feeding at the trough – is absent from Mr. Markey’s version(**). Instead of an absolute cap, the Markey bill’s performance test takes a more flexible, incentive-based approach. Likewise, Ms. Ernst’s idea to limit how many proposals a company or principal investigator can submit to each solicitation (to discourage bulk submissions) did not make the cut. And while Ms. Ernst championed a new “Phase 1A” program reserved for first-time applicants (with agencies required to set aside 2.5% of SBIR funds for it), Mr. Markey’s bill does not explicitly create a Phase 1A. The SBIR fellowship initiative may serve a similar spirit of bringing in fresh blood, but it’s a different mechanism. These omissions suggest that Democrats and some Republicans found parts of Ms. Ernst’s plan too restrictive or unworkable. Mr. Markey’s compromise leans toward carrots over sticks – raising the SBIR budget pie, providing larger awards for top performers, and nudging laggards to improve – whereas Ms. Ernst initially wielded more sticks (strict caps and limits) to weed out abusers. The hope among negotiators is that the core principles of her reforms are preserved without alienating supporters of the program. “Negotiations will continue within the Six Corners over compromise legislation,” one small-business advocacy update noted in December, referring to the bipartisan leaders of the House and Senate committees involved(**). Both sides may yet make further adjustments, but Mr. Markey’s bill has set a foundation that significantly overlaps with Ms. Ernst’s priorities.

A Ticking Clock and Uncertain Path Forward

Even as a legislative solution takes shape, the SBIR/STTR programs face a time crunch. Since Oct. 1, the lapse in authorization has prevented agencies from issuing new SBIR/STTR awards or new solicitations, freezing out startups that rely on these grants to develop innovative technologies(**)(**). Agencies are treading water: most continue honoring existing multi-year awards, but some, like the National Institutes of Health, have gone so far as to cancel or “early-expire” SBIR funding announcements because no reauthorization is in sight. NIH warned it will not even issue noncompeting continuation awards until the program is revived(**). This climate of uncertainty is exactly what lawmakers hoped to avoid. “A lapse creates uncertainty for innovators and risks slowing progress at a time when global competition is intensifying,” bipartisan leaders of the House Science and Small Business Committees said in a joint statement, condemning the Senate stalemate(**). By the House’s estimate, research is being delayed, innovation diminished, and America’s competitive edge eroded each day the program sits idle.

The House, in fact, did its part to avert this scenario. On September 15, the House unanimously passed H.R. 5100, a clean, one-year SBIR/STTR extension with no changes except to push the expiration to 2026(**). It was a straightforward bipartisan bid to keep the money flowing while debate continued on long-term reforms. But when that bill reached the Senate, it ran into an immovable object: Joni Ernst. As chair of the Senate Small Business Committee (a post she took when Republicans gained the majority in 2025), Ms. Ernst made clear she would block any extension “of any length” without immediate reforms(**). And block it she did. In a dramatic floor showdown on Sept. 30, hours before SBIR’s authority expired, Mr. Markey asked the Senate to approve H.R. 5100 by unanimous consent – only for Ms. Ernst to object, halting the bill. Ms. Ernst then countered with her own last-minute proposal: she sought to amend the extension down to just one month and splice in pieces of her reform package(**). This, in turn, drew an objection from Mr. Markey, who had previously voiced opposition to several of Ms. Ernst’s major changes. The end result: nothing passed, and SBIR/STTR authorization lapsed at midnight.

Since that cliffhanger, negotiations have quietly continued behind the scenes to find a compromise palatable to both Ms. Ernst and the rest of the “six corners” – the chairs and ranking members of the House and Senate committees with jurisdiction. By all accounts, Ms. Ernst’s buy-in is the linchpin. Five of the six relevant committee leaders (Democrats and Republicans alike) were willing to accept the stopgap H.R. 5100 extension and hammer out reforms later. It was opposed only by Senator Ernst, who insisted on including her INNOVATE Act reforms up front. Short-term SBIR extensions are not unprecedented – during a previous impasse from 2009–2011, Congress passed 14 temporary SBIR continuations while hashing out a deal.

Now, with Mr. Markey’s compromise draft on the table, there is cautious optimism that an agreement can be reached in time to piggyback on a broader spending bill. The next critical window is the end of January, when a temporary government funding measure is set to expire. Lawmakers face a January 30 deadline to pass an the government funding deadline (current continuing appropriations expire Jan. 30, 2026) (or another stopgap) to avert a shutdown. Capitol Hill insiders say this could be the vehicle to “hitch a ride” for SBIR reauthorization, if negotiators strike a deal in the coming weeks(**). Attaching the SBIR measure to a must-pass appropriations omnibus would virtually guarantee its enactment, riding along with funding for agencies like the Small Business Administration. Congressional leaders have used this approach before for expiring programs, especially when time is short and consensus has been achieved behind closed doors.

If the funding bill route falters, there is still the option of a standalone SBIR reauthorization – which could move astonishingly fast under unanimous consent, if all senators consent. That is exactly what happened in September 2022, during the program’s previous brush with death. In that episode, an 11th-hour deal (resolving a standoff with Sen. Rand Paul over foreign investment protections) cleared the Senate by unanimous consent just days before expiration, after which the House quickly gave its nod. Many on Capitol Hill haven’t forgotten that precedent. “In 2022, the last SBIR/STTR reauthorization passed as a stand-alone bill just days before the program was set to terminate,” the National Small Business Association reminded members in a recent update(**). If the negotiators – Senators Ernst and Markey chief among them – “can all agree on terms of a bill, [it] could be brought to the floor and quickly passed.”

As of early January 2026, the fate of America’s $4 billion-a-year small business research engine hangs on these negotiations. The introduction of Mr. Markey’s SBIR/STTR Reauthorization Act of 2025 – with its mix of reforms and program boosts – is seen as a significant step toward addressing Ms. Ernst’s concerns. The clock is ticking: each day without SBIR, promising startups are left in the lurch and federal research agencies are hamstrung in directing R&D funds. But if Senate negotiators can translate the Markey–Ernst compromise into legislative text that all sides accept, Congress could revive the storied program within the month – and perhaps secure its future for years to come.